| Irish Forums Message Discussion :: Union jack or the butchers apron |

| Irish Forums :: The Irish Message

Forums About Ireland and the Irish Community, For the Irish home and Abroad. Forums include- Irish Music, Irish History, The Irish Diaspora, Irish Culture, Irish Sports, Astrology, Mystic, Irish Ancestry, Genealogy, Irish Travel, Irish Reunited and Craic

|

|

Union jack or the butchers apron

|

|

|

| Irish

Author |

Union jack or the butchers apron Sceala Irish Craic Forum Irish Message |

jodonnell

Sceala Philosopher

Location: NYC

|

| Sceala Irish Craic Forum Discussion:

Union jack or the butchers apron

|

|

|

Some British consider the union jack a symbol of civilization, believe their flag represents democracy and freedom.

To many more people the union jack is known as the butchers apron. The british flag represents cruel and violent colonial oppression, british terrorist murder and enslavement of native peoples. To this group of people the union jack represents the most evil terrorist empire the world has ever witnessed. The British empire where the sun never set and the blood of innocents never dried.

Britania once ruled the waves, because it was built upon the money made being the worlds worst human slave trader and brutal terrorist colonizer. Native populations were massacred by the english and later british colonial terrorists.

Ancestor of African slave protests at British editing of history.

Toyin Agbetu interrupting a commemorative service at Westminster Abbey - marking the 200th anniversary of the act to abolish the slave trade - he did this to put the history record straight. The british empire was built on slavery and terrorism.

Toyin wanted to defend the memory of his Ancestors, who were victims of british terrorists. Protesting he tells the British queen the British have nothing to be proud of. He tells her, that to the Africans the British are Nazis, not liberators.

Concentration camps were named and invented by the British during the Boer War. The British also break all rules of Geneva convention.

All evil was for gold.

Did the British really believe in protecting the Africans from slavery?

Long after they claim to be the emancipator, events into the 20th century show a different story.

'To my mind the people of the embu have not been sufficiently hammered, I should like to go back at once and have another go at them'

'During the first phase of our expedition against the Iriani we killed 797 niggers'

'During the second phase against the embu we killed about 250' from the diary of a British officer stationed in Kenya.

And the genocide went on and on.

In the sixth campaign against the embu, british troops reported killing 1117 people, beside seizing all their livestock.

In 1906 a junior minister cabled this protest

'Surely it can not be necessary to go on killing these defenseless people on such an enormous scale'

Winston Churchill

who himself was hardly a notable humanitarian

The effect of British colonial rule in India

Gideon Polya

One can estimate that the 200 year British rule of India was associated with an excess [i.e. avoidable] mortality totalling 1.5 billion, making it the greatest racial crime in all of human history.

The butchers apron. The debate who is right

What is The Evil Empire?

In The Evil Empire, Steven A. Grasse exposes the secret history of England's global misdeeds. He asks what few have dared to ask: Having spent the better half of the millennium turning the world into their personal litter box, where do the English get off blaming everything on America?

After all, whose imperialistic shenanigans is Osama bin Laden really trying to avenge? Whose evil land grabbing greedy ways put the Irish, the Arabs, the Africans, the people of India and Pakistan, to the Palestinians and Israelis at each others throats? Who invented machine guns, wage slavery and concentration camps? The British empire did.

The closer you look at English history, the more you realize they're in no position to be pointing fingers. This outrageous indictment is sure to make blue bloods boil on both sides of the Atlantic.

Steven Grasse was interviewed by Stephen Nolan on BBC Radio Five Live about his forthcoming book, The Evil Empire: 101 Ways That England Ruined The World.

Watch this animated video of the interview to help shed light on some of the atrocities that The Evil Empire has committed.

The British reply

The effect of British colonial rule in India

Gideon Polya

One can estimate that the 200 year British rule of India was associated with an excess [i.e. avoidable] mortality totalling 1.5 billion, making it the greatest racial crime in all of human history.

This video is about the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, a cold-blooded murder of thousands of Indian men, women, and children who had peacefully gathered for celebrating a festival. The British who occupied India for about 200 years engaged in many cold-blooded masscares in the worst holocaust in the world. The Army General who ordered this particular masscare was knighted by the British queen. The place of the massacre in the city of Amritsar in the state of Punjab [India] still reminds you of what happened half a century back

In 1997 on a visit to India, Queen Elizabeth II Acknowledged the 1919 Amritsar Massacre but did not offer an Apology. Indeed the British have never apologized for anything they did during their appalling 2 century mis-rule of British India. While every Briton knows of the [largely fictional] Black Hole of Calcutta story that has demonized Indians for over 2 centuries, very few would be aware of the horrendous calamities inflicted on Indians by the British e.g. the 1769/1770 Great Bengal Famine [that killed 10 million, 1/3 of the over-taxed population of Bengal], further successive famines that killed scores of millions [the annual death rate in 1877 in British labour camps during the Deccan famine was about 94%, cholera epidemics spread by British mercantilism [that killed about 25 million Indians in the 19th century], extraordinarily low population growth between 1870 and 1930 [due to famine, malnourishment-exacerbated disease and cholera, plague and influenza epidemics], and the man-made, World War 2 Bengal Famine in British-ruled India [4 million victims, huge civilian and British military sexual abuse of starving women, a 1941-1951 Bengal demographic deficit of over 10 million ', and all of this largely deleted from British history, in part because it may have been due to a deliberate British ',scorched earth policy',].

The big picture of the impact of the British in India can be best assessed by measuring avoidable mortality [technically, excess mortality] which is the difference between the actual deaths in a country and the deaths expected for a peaceful, decently-run country with the same demographics .

The annual death rate in India as recently as 1920 was about 4.8% but this declined to 3.5% by 1947 and is presently about 0.9% [still about 2 times greater than it should be for a country with India',s demographics]. As a useful yardstick, the annual death rate of sheep on Australian sheep farms is about 2.5% i.e. the British were treating Indians like animals. Using a baseline ',expected', annual death rate value of 1.0% and assuming an ',actual', pre-1920 value of 4.8% one can estimated that the avoidable [excess] mortality was about 0.6 billion [1757-1837], 0.5 billion [1837-1901 i.e. during the reign of Queen Victoria] and 0.4 billion [1901-1947 i.e. from the turn of the century until Indian Independence].

Thus one can estimate that British rule of India was associated with an excess [i.e. avoidable] mortality totalling 1.5 billion ', surely one of the greatest crimes in all of human history.

The carnage did not end with the post-WW2 British departure from India and its other colonies egregiously crippled by colonial abuse ', thus the avoidable mortality in the mostly Third World British Commonwealth countries during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II [1953 to the present] has totalled about 0.7 billion.

How Britain Denies its Holocausts

Why do so few people know about the atrocities of empire?

By George Monbiot. Published in the Guardian 27th December 2005

As it prepares for accession, the Turkish government will discover that the other members of the European Union have found a more effective means of suppression. Without legal coercion, without the use of baying mobs to drive writers from their homes, we have developed an almost infinite capacity to forget our own atrocities.

Atrocities? Which atrocities? When a Turkish writer uses that word, everyone in Turkey knows what he is talking about, even if they deny it vehemently. But most British people will stare at you blankly. So let me give you two examples, both of which are as well documented as the Armenian genocide.

In his book Late Victorian Holocausts, published in 2001, Mike Davis tells the story of the famines which killed between 12 and 29 million Indians(1). These people were, he demonstrates, murdered by British state policy.

When an El Nino drought destituted the farmers of the Deccan plateau in 1876 there was a net surplus of rice and wheat in India. But the viceroy, Lord Lytton, insisted that nothing should prevent its export to England. In 1877 and 1878, at height of the famine, grain merchants exported a record 6.4 million hundredweight of wheat. As the peasants began to starve, government officials were ordered 'to discourage relief works in every possible way'(2). The Anti-Charitable Contributions Act of 1877 prohibited 'at the pain of imprisonment private relief donations that potentially interfered with the market fixing of grain prices.' The only relief permitted in most districts was hard labour, from which anyone in an advanced state of starvation was turned away. Within the labour camps, the workers were given less food than the inmates of Buchenwald. In 1877, monthly mortality in the British camps equated to an annual death rate of 94%.

As millions died, the imperial government launched 'a militarized campaign to collect the tax arrears accumulated during the drought.' The money, which ruined those who might otherwise have survived the famine, was used by Lytton to fund his war in Afghanistan. Even in places which had produced a crop surplus, the government's export policies, like Stalin's in the Ukraine, manufactured hunger. In the North-western provinces, Oud and the Punjab, which had brought in record harvests in the preceding three years, at least 1.25m died.

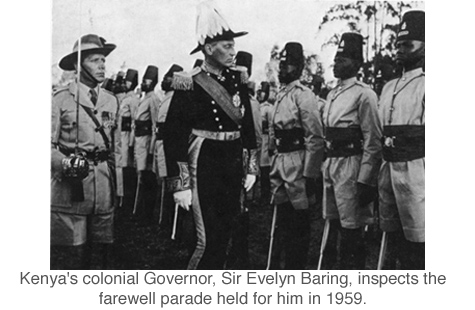

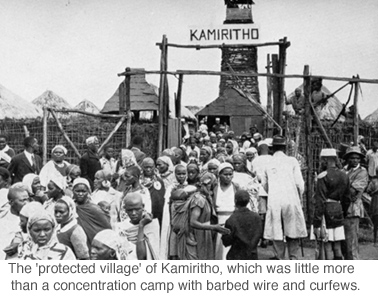

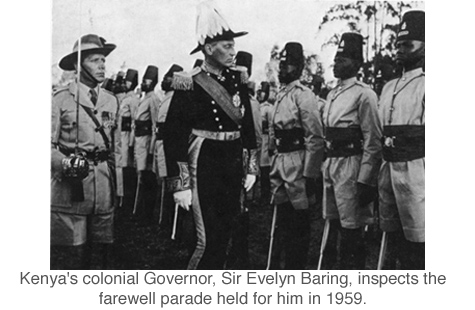

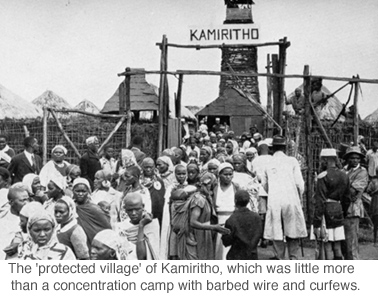

Three recent books - Britain's Gulag by Caroline Elkins, Histories of the Hanged by David Anderson and Web of Deceit by Mark Curtis - show how white settlers and British troops suppressed the Mau Mau revolt in Kenya in the 1950s. Thrown off their best land and deprived of political rights, the Kikuyu started to organise - some of them violently - against colonial rule.The British responded by driving up to 320,000 of them into concentration camps(3). Most of the remainder - over a million - were held in 'enclosed villages'. Prisoners were questioned with the help of 'slicing off ears, boring holes in eardrums, flogging until death, pouring paraffin over suspects who were then set alight, and burning eardrums with lit cigarettes.'(4) British soldiers used a 'metal castrating instrument' to cut off testicles and fingers. 'By the time I cut his balls off,' one settler boasted, 'he had no ears, and his eyeball, the right one, I think, was hanging out of its socket'(5). The soldiers were told they could shoot anyone they liked 'provided they were black'(6). Elkins's evidence suggests that over 100,000 Kikuyu were either killed by the British or died of disease and starvation in the camps. David Anderson documents the hanging of 1090 suspected rebels: far more than the French executed in Algeria(7). Thousands more were summarily executed by soldiers, who claimed they had 'failed to halt' when challenged.

These are just two examples of at least twenty such atrocities overseen and organised by the British government or British colonial settlers: they include, for example, the Tasmanian genocide, the use of collective punishment in Malaya, the bombing of villages in Oman, the dirty war in North Yemen, the evacuation of Diego Garcia. Some of them might trigger a vague, brainstem memory in a few thousand readers, but most people would have no idea what I'm talking about. In the Guardian today, Max laments our 'relative lack of interest in Stalin and Mao's crimes.'( 8 ) But at least we are aware that they happened.

In the Express we can read the historian Andrew arguing that for 'the vast majority of its half millennium-long history, the British Empire was an exemplary force for good. ' the British gave up their Empire largely without bloodshed, after having tried to educate their successor governments in the ways of democracy and representative institutions'(9)(presumably by locking up their future leaders). In the Sunday Telegraph, he insists that 'the British empire delivered astonishing growth rates, at least in those places fortunate enough to be coloured pink on the globe.'(10) (Compare this to Mike Davis's central finding, that 'there was no increase in India's per capita income from 1757 to 1947″, or to Prasannan Parthasarathi's demonstration that 'South Indian labourers had higher earnings than their British counterparts in the 18th century and lived lives of greater financial security.'(11)) In the Daily Telegraph, John Keegan asserts that 'the empire became in its last years highly benevolent and moralistic.' The Victorians 'set out to bring civilisation and good government to their colonies and to leave when they were no longer welcome. In almost every country, once coloured red on the map, they stuck to their resolve.'(12)

There is one, rightly sacred Holocaust in European history. All the others can be ignored, denied or belittled. As Mark Curtis points out, the dominant system of thought in Britain 'promotes one key concept that underpins everything else - the idea of Britain's basic benevolence. ' Criticism of foreign policies is certainly possible, and normal, but within narrow limits which show 'exceptions' to, or 'mistakes' in, promoting the rule of basic benevolence.'(13) This idea, I fear, is the true 'sense of British cultural identity' whose alleged loss Max laments today. No judge or censor is required to enforce it. The men who own the papers simply commission the stories they want to read.

Turkey's accession to the European Union, now jeopardised by the trial of Orhan Pamuk, requires not that it comes to terms with its atrocities; only that it permits its writers to rage impotently against them. If the government wants the genocide of the Armenians to be forgotten, it should drop its censorship laws and let people say what they want. It needs only allow Richard Desmond and the Barclay brothers to buy up its newspapers, and the past will never trouble it again.

References:

1. Mike Davis, 2001. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World. Verso, London.

2. An order from the lieutenant-governor Sir George Couper to his district officers. Quoted in Mike Davis, ibid.

3. Caroline Elkins, 2005. Britain's Gulag: The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya. Jonathan Cape, London.

4. Mark Curtis, 2003. Web of Deceit: Britain's Real Role in the World. Vintage, London.

5. Caroline Elkins, ibid.

6. Mark Curtis, ibid.

7. David Anderson, 2005. Histories of the Hanged: Britain's Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire. Weidenfeld, London.

8. 27th December 2005. This is the country of Drake and Pepys, not Shaka Zulu. The Guardian

9. Andrew Roberts, 13th July 2004. We Should Take Pride in Britain's Empire Past. The Express.

10. Andrew Roberts, 16th January 2005. Why we need empires. The Sunday Telegraph.

11. Prasannan Parthasarathi, 1998. Rethinking wages and competitiveness in Eighteenth-Century Britain and South India. Past and Present 158. Quoted by Mike Davis, ibid.

12. John Keegan, 14th July 2004. The Empire is Worthy of Honour. The Daily Telegraph.

13. Mark Curtis, ibid.

Britain's role in the slave trade

Prime Minister Tony Blair has voiced his "deep sorrow" over Britain's role in the slave trade that helped Britain become one of the world's greatest powers in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Soon after the discovery of North America and the setting up of British colonies, the native population had been decimated by disease. The Crown began the wholesale transportation of African slaves to work in the colonies.

Slaves in the British colonies in the Caribbean worked on the sugar plantations which helped make the empire rich.

During the course of the 18th century the British perfected the Atlantic slave system. It is thought between 1700 and 1810 British merchants transported almost three million Africans across the Atlantic. More than 30,000 slave voyages took place.

Miserable conditions

Some historians have argued that the transatlantic slave trade created the bedrock for the modern capitalist system, creating immense wealth for the British companies which ran it.

Cities such as Bristol, London and Liverpool grew rich off the trade.

The slaves included not only Africans but men arrested after a Royalist uprising in the West Country in 1655, and Irish captured by Oliver Cromwell.

Much of Bristol's 18th Century wealth came from the slave trade

Slaves were transported in miserable conditions, crowded into cargo holds and with little access to fresh air, clean water or proper food. Many died on the way.

Though Britain abolished slavery in 1807, it did not emancipate slaves in its overseas territories until 1834. Truth was cheap labour of the industrial revolution had made slavery expensive. The British empire could now use the masses of poor people in her many colonies as effective slaves in all but name, to provide foods and resources for London and the Monarchy to profit.

The truth about the British in Africa.

Kenya or Ulster, the evil ways of the British are the same.

The Myth of 'Mau Mau'

State Murder in Kenya

Africa was the last of the great continents to be fully opened up to colonisation, before which only a few white explorers, missionaries and traders had penetrated the core. Prior to the last two decades of the 19th century, western countries had directly ruled only a few coastal areas - with most of the interior under African control. Then steam power, especially for rail and ships, provided the means to open the continent up to foreign invasion and Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Spain and Portugal competed for territory. Africa then became a patchwork of new provinces, with most of its peoples coming under the control of the new colonial masters.

At the end of the 19th century, Britain had opened East Africa up for colonisation by the building of roads and railways. Strategic forts were built and African opposition was met with force, with tribes people who tried to stop the railways being machine-gunned. Tens of thousands of Africans were massacred and many more driven from their land. Kenya, as a country, emerged from the European 'scramble for Africa', which divided the continent into 'spheres of influence'. The 1884/5 Berlin Conference and later colonial agreements and adjustments deciding borders, which were then plotted by colonial bureaucrats ' rather than them developing from interaction between the native peoples.

Most of the Kenyan peoples, including the Kikuyu, Akamba, Maasai, Luo, Meru and Embu, were opposed to foreign rule and, as in other colonies, efforts were then made to win over some sections of the native population to the colonisers' side. This usually took the form of securing agreements with, or instating, local collaborationist tribal chiefs - whose main tasks then were to facilitate colonial rule and collect taxes. The Kikuyu tribe explained that they had no chiefs but were organised by age groups which reflected seniority. The colonial authorities ignored this tradition of clan elders and put in place chiefs who were paid and controlled by the British.

Kenya held no large deposits of natural resources, but it had strategic importance and parts of the land ' especially in the highland region ' was conducive to productive farming. All land was designated 'Crown land', which was then parcelled up into 'tribal reserves' ' with large parts of the best land being retained for colonists from Britain. The native peoples, including many Kikuyu, were then forced from this fertile land to make way for white settlers:

The early settlers, encouraged by the British government, who began arriving in substantial numbers after 1902, faced years of hardship and danger in building up prosperous farms in the 'White Highlands' of the Rift Valley. By the end of the Second World War they had succeeded in creating a landscape of huge estates and handsome houses.

Able to command squads of African labourers and servants, they shared a sense of citizenship in an improved version of England on the equator and prided themselves on their gracious living and vigorous sportsmanship. Polo flourished and five packs of hounds catered for the scarlet-coated hunting enthusiasts. The settlers also acquired a considerable reputation for hard drinking. ... It was a land, too, of fabled loose living ... One area of the White Highlands was even known as Happy Valley because of its reputation for light-hearted adultery and wife-swapping.[1]

About the time of the 1st World War some Africans, especially Kikuyu, were allowed to return to the white areas, but they were designated as 'squatters' and were then forced, with other Africans from the 'tribal reserves', into wage-labour to work the land under its new owners. To ensure Africans would not have an alternative method of earning money, they were prohibited from growing cash crops like coffee. New 'pass laws' then increased the authorities control over Africans, helping to augment the near feudal conditions under which they laboured: 'The authorities imposed hut and poll taxes which the blacks could pay only by working on the white man's farms. The settlers themselves demanded legalised methods of compulsion and the right to flog their black workers.' [2]

1: The British Empire,

Volume 6,

Ferndale Editions, London, 1981.

2: Ibid - The British Empire,

Volume 6.

Repression and Resistance

Kenya was in many ways like England after the Norman invasion, with the white settler barons treating the African people as serfs ' driving them through laws and taxes into forced labour. Unsurprisingly, sign of revolt began to show. In the years following the 1st World War Harry Thuku, a low paid telephone operator, formed the Young Kikuyu Association to campaign against the mounting hut taxes and an end to the pass laws. He was sacked from his job and then arrested and deported to the desert region in the north of the country. At a protest meeting in the capital, Nairobi, a number of Africans were shot down, while cheering white settlers looked on ' this occurred just over three years after the massacre at Amritsar in India.

Over 100,000 Africans from Kenya served in Britain's forces during the 2nd World War, often fighting alongside white troops. But afterwards, on their return home, they were offered only menial jobs under whites who called them 'boys' and treated them like slaves. Africans still had no worthwhile representation on any level of government and in the capital, Nairobi, black workers, fighting for better wages and conditions, organised themselves into trade unions. The East African TUC, set up by a number of these unions, called for African political independence and majority rule in Kenya.

In May 1950, the authorities arrested the leaders and banned many of the trade unions, including the East African TUC. A general strike, which led to a shut-down of large parts of the country, was called, but the strike was broken with mass arrests and large scale intimidation from British police and troops with armoured cars, supported by low-flying war planes. Hemmed in by repressive laws and with their economic conditions getting steadily worse, Africans found that their peaceful political protests about land rights in the countryside and the right of workers to organise into trade unions in the towns were being suppressed by armed force.

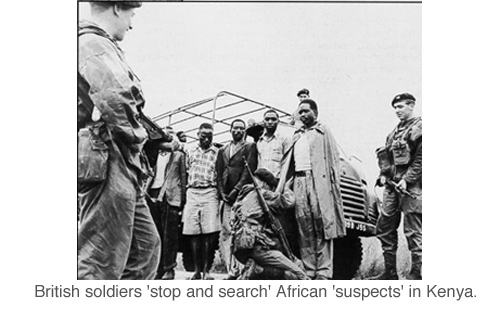

Not content with this level of repression, the authorities then declared a 'State of Emergency' on 20th October 1952, implemented even more repressive laws, built up local police and militias and sent for reinforcements of British troops. With all routes to constitutional reforms blocked off Africans, in steadily increasing numbers, began to support the emergent underground revolutionary movement, known to them at first as the 'Movement' or 'Unifier' and later in its armed stage as the 'Land and Freedom Army.'

As part of the counter-insurgency campaign then mounted against the opposition to colonial rule, the British authorities, using their control of the media, ensured that the underground movement of Africans would became known to the outside world as 'Mau Mau'. The words did not mean anything in any African language, and probably first came into use when whites misheard a local dialect. 'Mau Mau' conjured up images of an African 'heart of darkness' in susceptible western minds, and quickly gained widespread usage both within and outside Kenya. The spread of the name was helped by Government agencies and this successful psychological warfare operation made it easier to dehumanise the organisation in future years.

Moderate nationalists, many of whom had appealed to the authorities to allow a few concessions that might have halted the drift into conflict, were silenced or rounded up and jailed. The leading nationalist politician Jomo Kenyatta, who had denounced the use of violence by the militants, was arrested and convicted after a show trial of being 'the leader of Mau Mau', and was sentenced to imprisonment for 7 years. Josiah M. Kariuki, who was also interned in prison camps from 1953 to 1960, later stated:

After the 1939-45 War things were changing. Our social and economic grievances were plainer to all and there were many more educated Africans who were beginning to understand that the social system was not immutable. Most of all was this happening among my own tribe, the Kikuyu ... Normal political methods ... seemed to be getting nowhere. The young men of the tribe saw that a time of crisis was approaching when great suffering might be necessary to achieve what they believed in...

Although the situation was dangerous, even in October 1952, it was not so dangerous that it could not have been put right by a few political concessions ... But the Government chose to answer it with a series of the harshest and most brutal measures ever taken against a native people in the British Empire in the twentieth century, and so the movement developed by action and reaction into a full-scale rebellion involving the soul of my people...[3]

Many Africans who were left became increasingly more militant. Land and Freedom Army activists were forced to operate undercover, or from bases in the jungle-covered mountains and foothills of the highlands. Kariuki later talked about the Land and Freedom Army saying that: 'The world knows it by a title of abuse and ridicule [Mau Mau] with which it was described by one of its bitterest opponents.'

3: The Dissolution of the Colonial Empires,

by Franz Ansprenger,

Routledge 1989.

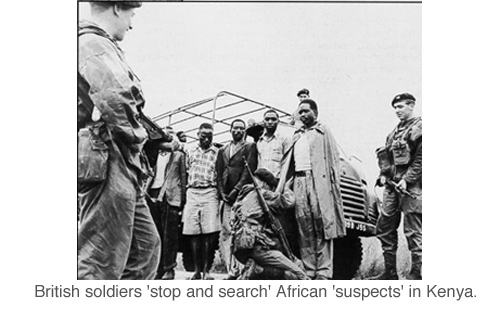

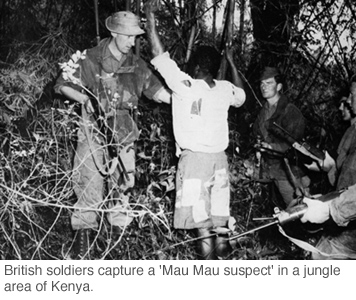

Shooting Orders

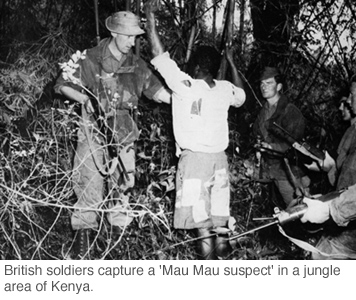

The settlers had long been angered by the growing 'insubordination' among the 'Kukes' (Kikuyu), because of the long history of their opposition to British rule. Many Kikuyu had resisted attempts by missionaries to change their local customs and traditions. Some also refused to send their children to mission schools, which they saw as perpetuating the colonial system, and organised their own independent schools instead. Settler xenophobia deepened, especially after attacks were made on a few isolated farms and some whites were killed. Considerable political pressure was exerted on the British authorities by the settlers and a shoot to kill policy was implemented.

In 'Prohibited Areas' any African could be shot dead, in other areas they could be challenged and shot if they did not halt. The settlers were delighted with their 'shooting orders'; in the past they had spoken about 'wiping out the Kukes'. At a public meeting at Nakuru it had been seriously proposed that '50,000 Kukes' be killed 'to set an example'. Now, after the killings were officially sanctioned, some whites brought in bounty hunters to carry out the 'exterminating' for them:

Some settlers hired other Africans to do their killing for them. The practice of paying Wanderobo hunters 20 shillings for every presumed Mau Mau they killed became so open that it was reported in the United States press. Other whites did their own 'exterminating'. Several professional hunters began to stalk Kikuyu just as they would some relatively dangerous game. One hunter, who was not usually given to braggadocio, said that he had killed more than 100 Kikuyu whom he thought to be Mau Mau, although he admitted that his policy of 'shooting first and asking questions later' made it difficult to be certain.[4]

Settlers themselves began to take drastic action against any suspect Africans, especially 'Kukes'. Brutality against blacks and murders of them became commonplace. For his book, Mau Mau: An African Crucible, Robert B. Edgerton interviewed an Australian who had fought with the Chindits in Burma during the 2nd World War. Living in Kenya during the 'Emergency' he had witnessed the killing of Africans when visiting a settler called Bill. After receiving a call that some 'Mickeys' [Mau Mau] were in the area, they armed themselves and rushed out to join the hunt:

We was joined by two of Bill's mates in another Land Rover and just about dawn we seen two Africans crossing the road ahead. Bill fired a shot across their bow and they put their hands up. I tried to tell Bill that those lads, hardly more than boys they was, didn't look like Mickeys to me but he says, 'They're Kukes and that's enough for me'. Well he roughs them up some but they say they don't know where the gang of Mickeys went to, so he gets some rope and ties one to the rear bumper of his Land Rover by his ankles. He drives off a little ways, not too fast you know, and the poor black bastard is trying to keep from ploughing the road with his nose. The other cobbers are laughing and saying, 'put it in high gear Bill' and such as that, but Bill gets out and says, 'Last chance, Nugu (baboon), where's that gang?' The African boy keeps saying he's not Mau Mau, but Bill takes off like a bat out of hell. When he comes back, the nigger wasn't much more than pulp. He didn't have any face left at all. So Bill and his mates tie the other one to the bumper and ask him the same question. He's begging them to let him go but old Bill takes off again and after a while he comes back with another dead Mickey. They just left the two of them there in the road.[5]

Afterwards they went off to a bar for lunch: 'Bill ordered beers all around. I was feeling a little shaky but I drank my beer, The other blokes was laughing and feeling fine as near as I could tell. Bill says, 'How do you think one of those Mickeys would've looked if I'd had him stuffed and mounted?' One of his mates says, 'You mean when he still had a face or after?' Another one says, 'Hell, he was better looking afterwards'. They had a good laugh over that. I spent the war with Wingate in Burma and I met some rough cobbers but I never seen men as cold as Bill and his mates was.'

4: Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

by Robert B Edgerton,

The Free Press, Collier Macmillan London 1989.

5: Ibid - Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

by Robert B Edgerton.

State Brutality

Karigo Muchai was an African who had also fought against the Japanese in Burma in the British forces. Back in Kenya he became involved in the struggle for freedom. He tells what happened after he was arrested and 'taken to the police post which held about 400 prisoners and was run by a brutal European officer nicknamed 'Kihara'':

I was to spend a month in this police post doing forced labour during the day and never knowing which night might be my last. 'Kihara' had a strange and terrifying game, which he practised daily. At any time he might come into one of the cells and read two or three names off the police register. No one knew when his name might be called and all of us lived in constant fear. Those called were tied up and thrown into a Land-Rover. 'Kihara' would then drive to the home of one of the prisoners, call his family out and in the presence of all, put a bullet through the head of his helpless captive. Leaving the dead body for the family to bury he would drive off to the next house where the same process was repeated.[6]

Many of the settlers were members of the local security forces, including the Kenya Police Reserve and Kenya Regiment. In these units, with white officers and native lower ranks, killings and ill treatment of black civilians became commonplace. The King's African Rifles (KAR), which recruited native soldiers from all over East Africa, quickly gained a reputation for brutality in prosecuting the war: 'The KAR were the first to be accused of atrocities. KAR troops, like those of the Kenya Regiment, routinely burned the houses of Kikuyu who were thought to sympathise with the Mau Mau, and it was KAR troops under the direct command of white officers who were said to have shot more than 90 prisoners in cold blood in what came to be known to the Mau Mau as the Kagahwe River massacre.' [7]

Idi Amin, from Uganda, served as a soldier with the KAR in Kenya. A contemporary, Dr. Atieno Odhiambo, described Amin as 'just the type the British liked, the type of African that they used to refer to as from the 'warrior tribes': black, big, uncouth, uneducated and willing to obey orders.' [8] A British officer said of Amin: 'Not much grey matter, but a splendid chap to have about.'

It was in Kenya that Amin learned many of the brutal practices that he would employ against his own people in Uganda many years later: 'Whether under orders by white officers or not, KAR soldiers often treated wounded Mau Mau by casually shooting or bayoneting them, or throwing them on top of dead Mau Mau in the back of a truck before driving off on a long journey during which the wounded either died on their own or were helped to do so.' [9]

6: The Hardcore,

the story of Karigo Muchai,

LSM Press - Canada1973.

7: Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

by Robert B Edgerton,

The Free Press, Collier Macmillan London 1989.

8: Lust to Kill - the Rise and Fall of Idi Amin,

by Joseph Kamau and Andrew Cameron,

Corgi 1979.

9: Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

by Robert B Edgerton,

The Free Press, Collier Macmillan London 1989.

Is Your Son a Murderer?

It was into this situation that reinforcements of British troops were rushed in 1952, many of them conscripts doing their National Service. Officers often found they had a natural affinity with the white Kenyans and spent much of their time-off at settlers' homes and clubs. Most ordinary soldiers knew nothing about Kenya or why the 'Emergency' was happening, but many had similar racist views to the settlers:

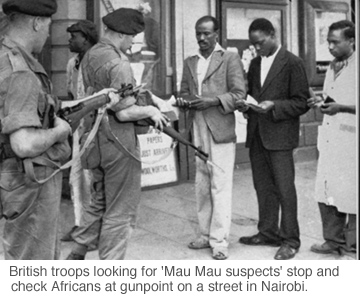

Most of these officers and men had left Britain with firm convictions about the racial superiority of whites (especially those from the Ireland and her surrounding islands), and their service overseas in places like Egypt, Cyprus, Palestine, and Malaya had only confirmed for them that 'wogs' and 'niggers' were a lower form of life. These attitudes were incorporated in a British Army Handbook, which was distributed to all officers. Under a section discussing the handling of African trackers assigned to Army units, it read: 'The African is simple, not very intelligent, but very willing if treated in the right way. Do not regard him as a slave or an equal. You will find that most Africans have an innate respect for the white man.'[10]

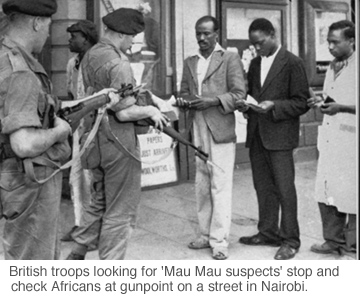

These racist attitudes, combined with their indoctrination and the 'Emergency' situation, showed up in the soldiers' actions: 'British soldiers were demonstrating their dislike for the Mau Mau in the streets of Nairobi. Some soldiers, usually after drinking, stopped Africans at random, beat them, and stole whatever valuables they possessed.' [11] Army battalions who were stationed close to 'Prohibited Areas', which included the jungle-clad mountains and the surrounding scrub-land foothills where many Africans had settled after being forced from their fertile land, quickly sought to prove their effectiveness by recording 'kills'. Africans detected in a 'Prohibited Area' - just like the 'Free Fire Zones' used by the US in Vietnam - were deemed to be 'hostile' and could be shot.

Many officers considered their units to be more professional than the local security forces and set about proving their superiority:

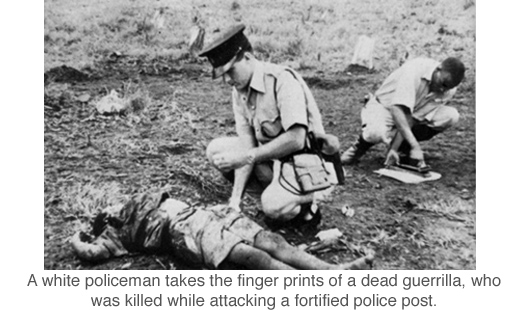

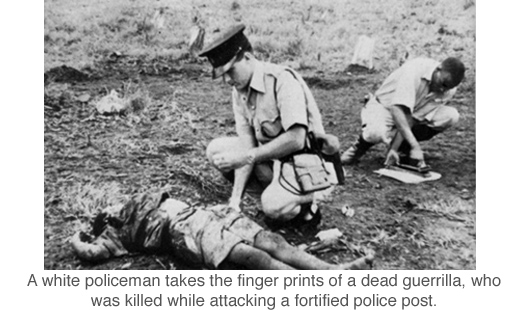

Units set up scoreboards showing their kills, and officers offered a bounty for each company's first kill, usually '5. Kills had to be confirmed, of course, and carrying a dead body back for identification was definitely not a pleasant duty, so hands were cut off and brought back as proof that a Mau Mau rebel - or someone, at least - had been killed. In principle, these hands could be used to identify the deceased Mau Mau through fingerprints, but since very few fingerprints of Mau Mau suspects existed in police files it was difficult to claim that the hands were cut off only as evidence.[12]

Back in Britain in early 1954 the Daily Herald carried a story about soldiers being paid for kills, under the headline: 'IS YOUR SON A MURDERER?' The regimental magazine of the Devons had mentioned the practice and questions were asked in the House of Commons. The War Office quickly convened a court of inquiry that exonerated British troops of any wrongdoing.

In Kenya, General Erskine expressed concerned about the Army's image and issued an official warning to his troops: 'It must be most clearly understood that the Security Forces under my command are disciplined forces who know how to behave in circumstances which are most distasteful.' Erskine continued:

I will not tolerate breaches of discipline leading to unfair treatment of anybody. We have a very difficult task and I have no intention of tying the hands of the Security Forces by orders and rules which make it impossible for them to carry out their duty - I am a practical soldier enough to know that mistakes can be made and nobody need fear my lack of support if a mistake is committed in good faith. But I most strongly disapprove of 'beating up' the inhabitants of this country just because they are the inhabitants. I hope this has not happened in the past and will not happen in the future...[13]

The warning did little to curb excesses and most practices continued covertly, with army units still keeping kills scoreboards - but now secretly. Erskine's public statement was contradicted by the views expressed in his letters home: 'Although Erskine referred to the practice of 'beating up' Africans, he privately admitted that much worse had been going on, telling his wife that 'there had been a lot of indiscriminate shooting' before his arrival.' Other correspondence with his superior, Field-Marshal Sir John Harding, the Commander-in-Chief of the Middle-East Command, was also revealing:

His [Erskine's] overall attitude was reflected in his injunction to Harding to resist the woolly liberal cry, 'Don't be too beastly to the Mau Mau'. On the one hand he claimed that Mau Mau adherents could be 'easily identified as they have long hair, long beards, and are filthy dirty' and that 'locals [were] entirely satisfied when we kill this type' - thus justifying a more discriminating 'shoot-to-kill' policy in the prohibited areas. On the other hand, he also rationalized pattern bombing of the prohibited areas - despite the indiscriminate deaths this would bring - on the grounds that if these areas were renamed as a 'bombing range nobody would attempt to waste their time and sympathy with people who deliberately chose to live in a bombing range'.[14]

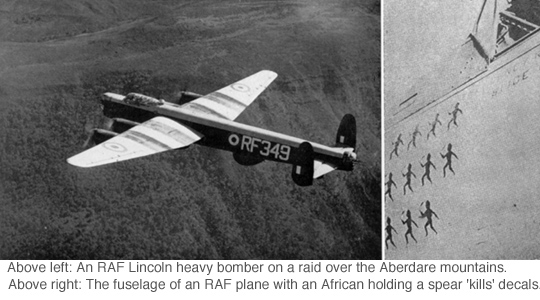

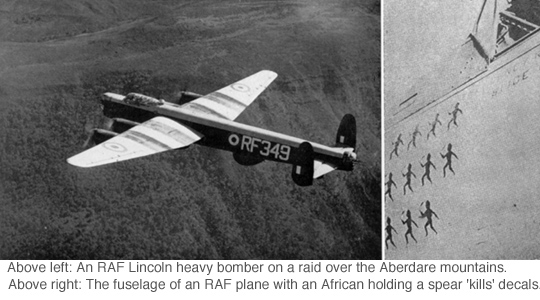

During the 'Emergency' British aircraft dropped 50,000 tons of bombs on 'Prohibited Areas'. They also fired over 2 million machine-gun rounds. Inevitably, many civilians as well as insurgents were killed and injured. RAF units, like Army regiments, kept a score of 'kills': 'While some British soldiers were cutting off hands and sometimes ears as trophies of war, British airmen in the Royal Air Force were decorating their aircraft with their own trophies. Instead of the 'kill' decals that in previous wars showed downed enemy aircraft, their decals pictured an African holding a spear.' [15]

10: Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

by Robert B Edgerton,

The Free Press, Collier Macmillan London 1989.

11: Ibid - Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

by Robert B Edgerton.

12: Ibid - Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

by Robert B Edgerton.

13: Counter Insurgency in Kenya 1952-60,

by Anthony Clayton,

Transafrica Publishers 1976.

14: Winning Hearts and Minds,

by Susan L Carruthers,

Leicester University Press 1995.

15: Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

by Robert B Edgerton,

The Free Press, Collier Macmillan London 1989.

Bringing the War Home

In the post 2nd World War years the British Army was made up of regulars and conscripts. Most soldiers in colonial conflicts obeyed their orders and carried out what they saw as their duty. Some, carried away on a tide of indoctrination and jingoism, believed passionately in what they were doing. In 1977, a disabled Scottish ex-soldier, who signed on as regular soldier just after the end of the 2nd World War, wrote about his experiences in some of these small wars:

It is getting along to 30 years since I first signed on as a regular. I was out of work, and in trouble with the police. The army was much bigger in those days. Once in it I was convinced there was no way they would get me back to the slums of Glasgow. My own bed and locker. Good clean clothes. Plenty of good grub. Great comradeship from the men in my billet. What more could a young man ask? I had known poverty and hunger all my boyhood days. The army was a great life for me. It is hard for young working-class men to realise the attractions of such a life, unless they have known similar poverty and hunger.

In those days the army fought 'the dirty commies'. We shot 'the yellow slant-eyed bastards' in the hills of Korea, chasing him back to the Yalu River, where 'some bastard politician' stopped us from going over and finishing them off for good. We went into the jungles of Malaya, and 'routed them out'. It cut us to the quick to see 'that evil bastard' Chin Peng get all that cash for surrendering. He and his will-o'-the-wisps had given us a lot of trouble and sweat. Now the government was giving him a load of cash. It was crazy. If they'd turned him over to us we would have chopped him up into little cubes and fed him to the dogs that ran around in packs in Kuala Lumpur.

Out in Kenya we hated that 'black cannibal' Jomo Kenyatta. The officer from Intelligence who gave us our political lectures (did you know they gave such things in the British army?) told us Jomo wrote for the Commie paper, the Daily Worker. If we'd caught him in the forests of the Aberdares we would have chopped him up with blunt pangas.

In Cyprus we fought that 'little murdering bastard' Grivas. It was strange how nobody would turn the 'little wall-eyed bastard' in. It did not matter how much we kicked and beat them. The Greek Cypriots would never divulge his hiding place.

Came the day when I copped a packet. It was not pleasant. They took me on a stretcher, all strapped down, and flew me back for medical attention. I was paralysed from the waist down. Every jolt I got caused racking pains to tear through my body. Lying beside me on the plane was a young Scottish lad. He came from my native city of Glasgow. I guess they put him beside me because I spoke 'Glasca' like him. Maybe they thought the sound of his native accent would quieten him down. He was as mad as the proverbial mad hatter. When he looked at me out of his mad eyes, I felt myself shrink back in fear. After all, I was only an arm's length away from him, and partially paralysed.

In different hospitals in various countries, experts prodded and poked me. They caused me a lot of pain. But months later I was still affected with terrific pain if I got any sudden movements. I went back to civvy street like an old man - shuffle-shuffle. It was in the Union Jack Club opposite Waterloo Station that my position was brought home to me. A young soldier like myself was lying dead drunk. His documents had fallen out of his jacket. I saw he had been in places out East that I had just been in. He was discharged just like me. But he could get no work.

I felt a wave of despair wash over me. How could I survive? Back in Glasgow I went to sign on at the Labour Exchange. They had no work for ex-killers. 'So what if you do have ribbons from half a dozen campaigns? We need men who can work all day and every day. You can hardly walk!' These clerks were all throw-backs to the means test days. They could not even manage a look of pity for a young man with a pale face, all complete with dark rings under the eyes for added effect.

How I hated mankind. Here I was, reduced from being a hard soldier, six feet tall, twelve and a half stone in weight, down to nine stone something. Yet nobody gave a dam about it. Even the ex-Regulars Association would not attempt to find me a job. The fat bastard ex-sergeant major had just the job I could have done. Nobody would help me. I would have to look out for myself.

I made it. No thanks to the bastards who run the country. They took my youth and young manhood. Today I still suffer pain. But my muscles have toughened a lot. As of now, they are able to bear me up. But what will happen when I get old and they become less strong? I just don't fancy the idea of sitting out the remainder of my days in some establishment for infirm soldiers, raving about the days when we were young.

Oh! I forgot to tell you. I could not find a wife. You see, I am rendered impotent. Yip Ming was my last bed-mate. She was a Chinese prostitute I lived with, out in the Far East. She bore me two sons. But I could not marry her. The army would not permit it. She went back to China and I have lost touch with her. My sons will be in their twenties now. Probably they read the thoughts of Chairman Mao and curse their white-skinned father.[16]

Many other ex-soldiers suffered from physical and/or psychological wounds after leaving the army. Some brought home the violence they had been taught to dish out in colonial wars. Harry Roberts, convicted after the killing of three policemen on a west London street in 1966, and Donald Neilson - nicknamed the 'Black Panther' - who was convicted for four murders during a series of robberies and a kidnapping, were both ex-National Service men. Neilson had served in Kenya and Cyprus. Roberts, who had been a unit marksman, is a veteran of Malaya and Kenya.

A young British officer who had been involved in the fighting in Malaya said: 'We were shooting people. We were killing them. ... This was raw savage success. It was butchery. It was horror.' A National Serviceman who had served in Kenya said: 'In the Aberdare Forest you were allowed to shoot any black man - if he's black, you shoot him because he's Mau Mau - it was a prohibited area.' In jail Roberts told other ex-soldier prisoners he had once got into trouble for refusing to shoot an African in Kenya. He also spoke to a journalist who asked him why the policemen had been shot. Roberts replied: 'They're strangers, they're the enemy ... It's like people I killed in Malaya when I was in the army.' [17]

16: Socialist Worker,

12th Nov. 1977.

17: Hidden Wounds - The problems of the north of Ireland veterans in Civvy Street,

by Aly Renwick,

Barbed Wire 1999.

Divide and Rule

In Kenya the British authorities were still having difficulty containing the insurrection. While the level of anti-black brutality and repression did intimidate some Africans, many more became angry and threw their weight behind the resistance. Land and Freedom Army units were often led by black ex-soldiers who had fought in the British forces during the 2nd World War. Deep in the forests, they operated under British Army style discipline. Training and attacks occupied much of their time, but at night they sat around camp fires singing patriotic songs:

No African can sleep

Because of lack of adequate food.

We shall be happy

When we get our land back.

In great unity

The Kenyan people truly united

Let us now throw this colonial yoke off our backs

So we can find open fields in which to work and play.

We shall be very happy

When our oppressors are forced to agree

That we are masters of this land.

Today they call us 'boys'

Because they pretend not to know who we are!

Our fertile land was taken from us

We were forced into desert land

And still they continue to treat us

As if an African has no blood in his veins . [18]

Some Land and Freedom Army members likened themselves to the Wat Tyler led peasants in England, who had revolted against feudal laws and taxes. They also spoke of 'levelling' in Kenya in much the same way as had the Levellers in England, before they were suppressed by Cromwell after the Civil War. New fighters and supplies were smuggled to Land and Freedom Army units in the forest areas by African supporters outside. In the towns and countryside support was strong and unwavering. Black prostitutes, who often had security forces personnel as clients, sometimes charged soldiers and policemen rounds of ammunition for their services. These bullets were then smuggled to the fighters in the forests.

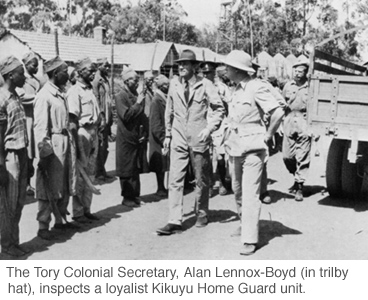

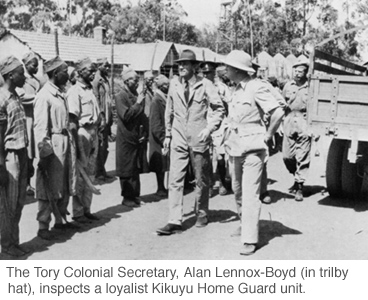

The authorities, using divide and rule tactics, succeeded in creating divisions within African society and although Akamba, Maasai, Luo, Meru and Embu militants did join the Land and Freedom Army, the movement remained overwhelmingly Kikuyu. Who were now themselves split between the nationalists, including Land and Freedom Army members and supporters who wanted land reform and an end to white rule and taxes; and the loyalists, mainly the appointed chiefs and their supporters, who sided with the whites. While land and crops were confiscated from many nationalists, restrictions on native land ownership and farming were lifted for loyalists - allowing many of them to become wealthy compared to other Africans.

Counter-insurgency strategists then deemed it a priority to break the support system and isolate the Land and Freedom Army units in the forests. To achieve these objectives the Kikuyu were now herded into 'reserve areas' and 'protected villages', which, following on from their predecessors in Malaya, were like mass prison camps. Africans were subject to the control within of loyalists organised into armed 'Home Guard' units, and outside by police and soldiers.

The Kikuyu Home Guard, instigated and protected by the white administration and under the control of loyalist chiefs, quickly gained a reputation for ruthless and corrupt behaviour. There were allegations of extortion rackets and their actions became so scandalous that even one of the white judges, Justice A. L. Cram, criticised them during a hearing: 'There exists a system of guard posts manned by headmen and chiefs, and these are interrogation centres and prisons to which the Queen's subjects, whether innocent or guilty, are led by armed men without warrant and detained - and as it seems tortured until they confess to alleged crimes and are led forth to trial on the sole evidence of these confessions ... [to] a hostile bench primed with lies, and the shadow of the cells, flaying whips and threats...' [19]

The enmity between the loyalists and the nationalists deepened and escalated into bloody fratricidal conflict. This was of great benefit to the British, as much Land and Freedom Army time and effort was now taken up with fighting the loyalists. The brunt of the war, from the British side, was now born by pro-white Africans and the conflict could be deemed a 'civil war' for propaganda purposes.

18: Thunder from the Mountains - Mau Mau Patriotic Songs,

edited by Maina wa Kinyatti,

Zed Press 1980.

19: Counter Insurgency in Kenya 1952-60,

by Anthony Clayton,

Transafrica Publishers 1976.

Oaths & Propaganda

The offensive against African resistance was accompanied by a propaganda campaign aimed at dehumanising 'Mau Mau' in the eyes of the world. During the struggle a massacre occurred at Lari, a village dominated by a wealthy pro-colonial chief who ruled over many displaced squatters living as landless tenants. Some local Land and Freedom Army members attacked and killed the loyalist chief and some of his family and followers also died after their huts were set on fire. Enraged by this the Home Guard, reinforced with police and soldiers who had entered the village and the surrounding area, took their revenge by killing hundreds of the poor landless tenants and burning a large number of their huts. Afterwards, government press releases spoke only of an attack 'by the bestial wave of Mau Mau' and blamed all the murders on 'terrorists insatiable for blood'. All the Lari killings then appeared in the western media as a 'Mau Mau atrocity'.

Throughout the conflict, government press handouts featured lurid accounts of the oaths that Land and Freedom Army volunteers took when joining the organisation. Oathing was a traditional practice within the age group system of Kikuyu society, and its use for the underground resistance movement was simply an extension of this. Josiah M. Kariuki stated: 'It is easy enough for anyone who knows my people to understand that it was a spontaneous decision that they should be bound together in unity by a simple oath. From what I have heard this oath began in the Kikuyu districts, starting in Kiambu. There was no central direction or control. The oath was not sophisticated or elaborate and initially was wholly unobjectionable...' [20]

Oaths had been tolerated by the white administration and often used by loyalist chiefs to control the population. Oaths are also used in many societies including Britain, where members of the armed forces, police and others swear allegiance to the reigning monarch. They are undertaken to maintain commitment through bonding, honour and fear. The Kikuyu were mainly a peasant people and their oathing practices reflected this. Those being initiated sometimes held a moist ball of earth to their stomach and a liquid mixture containing crushed grain, soil and animal blood was smeared on their foreheads in the shape of the cross. The oaths were often militant, but usually simple and straightforward:

Our African source confirms that he took two oaths at the end of 1953; first a political oath of allegiance, then the stronger oath of the fighter, who pledges to kill and to spill his own blood. He quotes the first oath as follows:

I speak the truth and vow before God

And before this movement,

The movement of Unity,

The Unity which is put to the test

The Unity that is mocked with the name of 'Mau Mau',

That I shall go forward to fight for the land,

The lands of Kirinyaga that we cultivated,

The lands which were taken by the Europeans.

And if I fail to do this

May this oath kill me...

He then quotes from the second oath:

I speak the truth and vow before our God:

If I am called to go to fight the enemy

Or to kill the enemy I shall go,

Even if the enemy be my father or mother,

My brother or sister

And if I refuse

May this oath kill me...[21]

The second oath was taken during the bitter struggle between the militants and the loyalist Kikuyu. The practice was made to appear repugnant, but the Land and Freedom Army oaths were no more extreme in Kikuyu society than the Freemasons oath - which is also couched in violent language and strange rituals - is in ours.

Concentrating peoples' minds on 'Mau Mau' oaths obscured the political nature of African opposition to British rule and played on western prejudices about 'witch doctors', evoking imagined images of the terrible and frightening practices of 'savages' in the dark jungles. Government propaganda fixed on this issue, portraying the 'Mau Mau' as a 'bestial, sub-human gang'.

20: The Dissolution of the Colonial Empires,

21: Ibid - The Dissolution of the Colonial Empires,

'Cleansing' the 'Mau Mau'

The first fruits of the propaganda campaign to dehumanise the 'Mau Mau' were seen in the increasingly brutal activities of the security forces. 'Screening', which was meant to uncover all Land and Freedom Army activists and supporters, quickly degenerated into callous torture as the interrogators tried to make the internees confess to have taken oaths. At all the camps the prisoners were brutally treated: 'They [the white screeners] hated the Mau Mau in principle and they hated the sullen, obstinate refusal of the detainees to confess having taken an oath. Day after day they gave vent to their hatred with a frenzy of punches, kicks, and blows from clubs, whips and rubber hoses.' [22]

The administration thought that the process of 'screening' - forcing a prisoner to confess to have taken an oath, followed by detention - would break and then 'cleanse' the 'Mau Mau'. During screening some detainees screamed with pain, but many refused to cry out or confess. Often detainees were beaten unconscious, some were beaten to death. One screening camp used a loyalist Kikuyu to castrate prisoners who refused to confess. Other brutal practices included burning with lit cigarettes, cutting off fingers and ears and soaking victims with paraffin, who were then set on fire.

Rather than 'cleansing' the 'Mau Mau', the process brutalised many interrogators. Some, like this Kenya police officer who led a screening team for several months, began to realise the consequences of their actions:

At first, they weren't human to me; they were black animals who had done inhuman things to women and children. I was bloody well going to beat the Mau Mau poison out of them. At the end of the day my hands would be bruised and arms would ache from smashing the black bastards. I hated them and sometimes I wanted to kill them. A few times I did, or we all did together. I never worked alone, it was always our whole lot together like a rugger scrum. I screened those bastards for four months, almost five, and only got a handful of confessions out of them. I'd been drinking too much for some time before I really tied on one at Manyani. The next morning I realised that they'd won. I hated myself for what I was doing more than I hated them. I finally had to admit that they were brave men who believed in what they were doing more than I believed in what I was doing. I resigned and got out of Kenya as fast as I could.[23]

Detainees who broke and admitted taking oaths often found a simple confession was not enough. In scenes reminiscent of the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries, the ill treatment of Africans continued till they confessed to lurid accounts of oath-taking that conformed to the stereotypes of this activity held in the minds of their captors. These confessions of 'bestial oath-taking' were then used as anti-'Mau Mau' propaganda by the authorities:

Material on Mau Mau oaths was ... supplied as an antidote to the criticism that Mau Mau arose from real political and economic grievances, and that Britain's repression of 'terrorism' was an inadequate response. For example, the Colonial Office seized upon the idea of providing India with lurid details of the oaths as the most suitable means of countering that country's 'misperceptions', H. T. Bourdillon writing:

'I think this a suitable opportunity to counter the Indian suggestion that Mau Mau is a popular and ultimately progressive liberation movement to which the complete solution is concessions by Her Majesty's Government, and in this connection to draw the Indian Government's attention to the notorious Mau Mau oaths and ceremonies, details of which will already have been or might simultaneously be given to them by the UK High Commissioner.'[24]

The background briefing issued to British soldiers arriving in Kenya also contained details of 'Mau Mau' oaths. Some detainees were forced to undertake anti-'Mau Mau' oaths as part of their 'rehabilitation'. These oaths were administrated by 'respectable' Africans, who were laughingly called 'Her Majesty's Witch Doctors' by the whites.

22: Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

23: Ibid - Mau Mau: An African Crucible,

24: Winning Hearts and Minds,

Executions & Internment

Sometimes British soldiers had to man firing posts on the edge of jungle areas, while 'loyalist' African 'beaters' hacked their way through the undergrowth towards them. 'Mau Mau' fleeing the 'beaters' were shot down by the waiting soldiers. The officers called these 'grouse drives'. Much of this repression was reminiscent of Ireland in 1798 at the time of the United Irishmen. Like in Ireland, a travelling gallows was used in Kenya to swiftly execute 'rebels'. Even in death, Africans were allowed no dignity:

White rage did not end when Mau Mau rebels were killed in action against security forces. The dead were typically treated with the utmost contempt. When Mau Mau were killed in the reserves, their bodies were lined up for public display. Sometimes they were photographed with their dead eyes staring into the lens of the camera. Afterwards the dead were often kicked, spat at, urinated on, and mutilated. When a prominent Mau Mau officer was killed, his body might be left on public display for days. White Kenya Police Reserve officers brought the body of General Nyoro back to the reserves and displayed it to the inhabitants. The police, who wanted to leave no doubt that his death was ignominious, kept the body on display for 48 hours as it swelled in the heat and dogs nibbled at it. Sometimes badly wounded Mau Mau were displayed to crowds of Kikuyu who were forced to look at the suffering rebels. After General Kago was wounded in one of the conflict's longest battles in 1954, he was captured and taken to the reserve where he was placed on a pyre, soaked with gasoline, and burned to death as horrified Kikuyu farmers were forced to watch.[25]

As Westminster MPs back home debated ending the death penalty in Britain, non-jury courts in Kenya were sentencing thousands of Africans to hang: 'Administering or ta

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|